Keep it Moving: How a Biomaterial Mobility May Revolutionize Immunomodulation

Researchers from Tokyo Medical and Dental University (TMDU) identify biomaterials that can be used to modulate liver immune cell behavior

Tokyo, Japan – Biomaterials are substances, natural or manmade, that are used in medicine to interact with the human body for various purposes, such as wound healing and tissue regeneration. Previous work on biomaterials has shown that they can affect cells in many ways, including how they grow, move, and the type of cell they develop into. Scientists have recently begun investigating biomaterials with properties that can be fine-tuned to optimize their use in regenerative medicine. Now, researchers at Tokyo Medical and Dental University (TMDU) have identified a polymer with tunable mobility properties that can alter the immune activity of specific liver cells.

In an article published in Biomaterials Science, the TMDU researchers report how they varied the mobility of specific biomaterials and observed significant effects on mouse Kupffer cells. These are liver cells that form part of the innate immune system—the body’s first line of defense against an infection in this organ.

The group previously worked with polymer-based biomaterials called polyrotaxane. Other molecules can be weaved within the polymer structure, and their ability to move freely throughout this structure is what the researchers refer to as “molecular mobility.” Polyrotaxane mobility can be adjusted by adding more molecules within the polymer, and this could affect the fate and maintenance of cells interacting with the biomaterials. Because of this, the TMDU group became interested in whether the biomaterials could be utilized to manipulate the immune system.

“We hypothesized that the polyrotaxane molecular mobility could serve as a sort of mechanical cue to the cells in the surrounding environment,” says lead author of the study Yoshinori Arisaka. “Using this property to possibly modulate immune cell activity could revolutionize immunomodulation.”

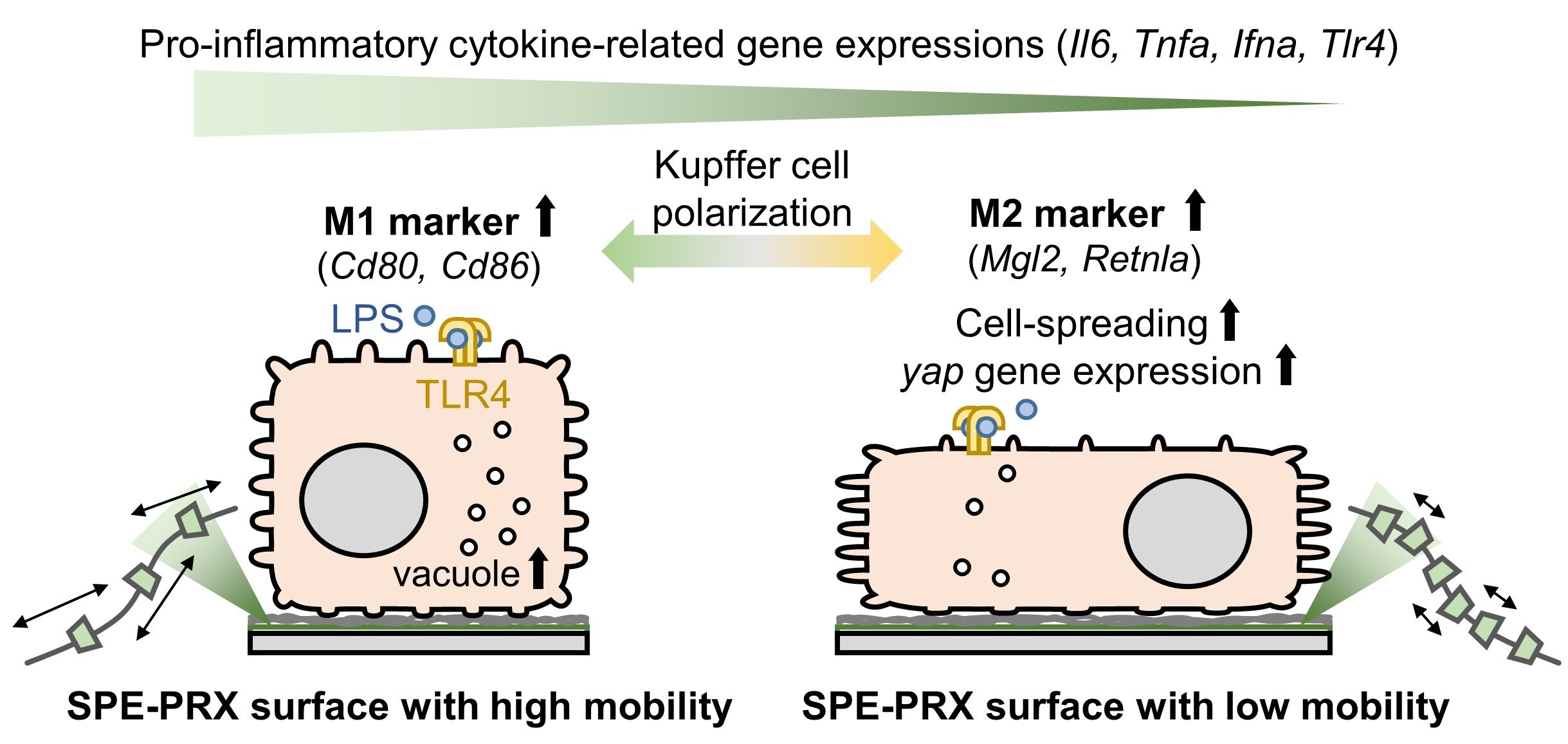

The researchers cultured Kupffer cells on a surface coated with polyrotaxane. They treated the cells with lipopolysaccharide, which is a molecule used as an immune activator. They adjusted the molecular mobility of the surface and then examined cell movement and shape, as well as the expression levels of certain inflammation-related genes. Interestingly, they found that the surface mobility significantly affected the movement and gene expression profile of the Kupffer cells.

“The surfaces with higher mobility increased expression of pro-inflammatory genes in the cells,” explains Nobuhiko Yui, senior author. “This means that the cells were behaving as if they were part of an active immune response.”

The authors believe that this system may be the groundwork for using biomaterials in humans to balance immune activity.

“Our data demonstrate that mechanical cues may play a role in regulating cell behavior,” says Arisaka.

This work is a critical step forward in biomaterials research. Mechanically regulating immune system activity with novel biomaterials may transform regenerative medicine.

Tokyo, Japan – Biomaterials are substances, natural or manmade, that are used in medicine to interact with the human body for various purposes, such as wound healing and tissue regeneration. Previous work on biomaterials has shown that they can affect cells in many ways, including how they grow, move, and the type of cell they develop into. Scientists have recently begun investigating biomaterials with properties that can be fine-tuned to optimize their use in regenerative medicine. Now, researchers at Tokyo Medical and Dental University (TMDU) have identified a polymer with tunable mobility properties that can alter the immune activity of specific liver cells.

In an article published in Biomaterials Science, the TMDU researchers report how they varied the mobility of specific biomaterials and observed significant effects on mouse Kupffer cells. These are liver cells that form part of the innate immune system—the body’s first line of defense against an infection in this organ.

The group previously worked with polymer-based biomaterials called polyrotaxane. Other molecules can be weaved within the polymer structure, and their ability to move freely throughout this structure is what the researchers refer to as “molecular mobility.” Polyrotaxane mobility can be adjusted by adding more molecules within the polymer, and this could affect the fate and maintenance of cells interacting with the biomaterials. Because of this, the TMDU group became interested in whether the biomaterials could be utilized to manipulate the immune system.

“We hypothesized that the polyrotaxane molecular mobility could serve as a sort of mechanical cue to the cells in the surrounding environment,” says lead author of the study Yoshinori Arisaka. “Using this property to possibly modulate immune cell activity could revolutionize immunomodulation.”

The researchers cultured Kupffer cells on a surface coated with polyrotaxane. They treated the cells with lipopolysaccharide, which is a molecule used as an immune activator. They adjusted the molecular mobility of the surface and then examined cell movement and shape, as well as the expression levels of certain inflammation-related genes. Interestingly, they found that the surface mobility significantly affected the movement and gene expression profile of the Kupffer cells.

“The surfaces with higher mobility increased expression of pro-inflammatory genes in the cells,” explains Nobuhiko Yui, senior author. “This means that the cells were behaving as if they were part of an active immune response.”

The authors believe that this system may be the groundwork for using biomaterials in humans to balance immune activity.

“Our data demonstrate that mechanical cues may play a role in regulating cell behavior,” says Arisaka.

This work is a critical step forward in biomaterials research. Mechanically regulating immune system activity with novel biomaterials may transform regenerative medicine.

Immune response of Kupffer cells depending on the molecular mobility of polyrotaxane (PRX) surfaces.

LPS-stimulated mouse Kupffer cells on PRX surfaces with high mobility had smaller areas of spread than those on PRX surfaces with low mobility, whereas the cells showed higher expression levels of Toll-like receptor 4 (Tlr4), M1 marker and pro-inflammatory cytokine genes, and frequently formed multiple cytoplasmic vacuoles in the their cytoplasms. In contrast, the LPS-stimulated Kupffer cells on PRX surfaces with low mobility had wider areas of spread, enhancing the expression of M2 marker and the Yap genes, while decreasing the expression of the pro-inflammatory genes. These results suggest that the highly mobile surfaces favor the M1 polarization of Kupffer cells, whereas less mobile surfaces favor the M2 polarization.

LPS-stimulated mouse Kupffer cells on PRX surfaces with high mobility had smaller areas of spread than those on PRX surfaces with low mobility, whereas the cells showed higher expression levels of Toll-like receptor 4 (Tlr4), M1 marker and pro-inflammatory cytokine genes, and frequently formed multiple cytoplasmic vacuoles in the their cytoplasms. In contrast, the LPS-stimulated Kupffer cells on PRX surfaces with low mobility had wider areas of spread, enhancing the expression of M2 marker and the Yap genes, while decreasing the expression of the pro-inflammatory genes. These results suggest that the highly mobile surfaces favor the M1 polarization of Kupffer cells, whereas less mobile surfaces favor the M2 polarization.

###

The article, “Molecular mobility of polyrotaxane-based biointerfaces alters inflammatory responses and polarization in Kupffer cell lines,” was published in Biomaterials Science at DOI: 10.1039/d0bm02127j Summary

Researchers from Tokyo Medical and Dental University (TMDU) have found that biomaterials with high molecular mobility can give mechanical cues to liver immune cells to induce an inflammatory response. Different polyrotaxane-coated surface mobilities resulted in varied cell responses. These valuable findings suggest that this technology could possibly be developed into a treatment for modulating immune system activity in humans, which could revolutionize immunomodulation and regenerative medicine.

Correspondence to

Nobuhiko Yui,Professor

Yoshinori Arisaka,Assistant Professor

Department of Organic Biomaterials,

Institute of Biomaterials and Bioengineering,

Tokyo Medical and Dental University (TMDU)

E-mail:yui.org(at)tmd.ac.jp

*Please change (at) in e-mail addresses to @ on sending your e-mail to contact personnels.

Yoshinori Arisaka,Assistant Professor

Department of Organic Biomaterials,

Institute of Biomaterials and Bioengineering,

Tokyo Medical and Dental University (TMDU)

E-mail:yui.org(at)tmd.ac.jp

*Please change (at) in e-mail addresses to @ on sending your e-mail to contact personnels.