"Adenoid and Tonsil Trouble for Teens"

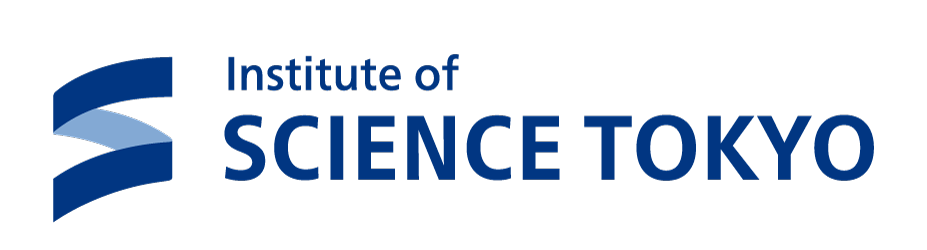

Tokyo, Japan – In the most thorough longitudinal study performed to date, X-ray images of children at five developmental stages between the ages of eight and nineteen were carefully measured (Fig. 1). The finding that the adenoids and tonsils do not shrink significantly during the teenage years may reshape the guidelines for when an adenotonsillectomy should be performed to treat respiratory complications, e.g., obstructive sleep apnea (OSA). The adenoids and tonsils are small regions of tissue at the back of the throat that help the body’s immune system fight ingested and inhaled pathogens. While the removal of inflamed adenoids and tonsils are often seen as a hazard of childhood, most people who have a tonsillectomy today do so to treat OSA. Patients with OSA often have trouble sleeping due to these enlarged tissues, and usually have the adenoids and tonsils surgically removed at the same time (adenotonsillectomy).

Since 1923, when Dr. Richard Scammon first published graphs of growth patterns in the human body, it has been the medical consensus that the lymphoid tissues, which include the adenoids and tonsils, peak in size around 12 years old, and then shrink to reach their adult shape by about age 20. Now, a study by a team led by researchers at Tokyo Medical and Dental University (TMDU) challenges this belief, and found that the adenoids and tonsils remain more or less constant in size from lower primary school through young adulthood. These results will be important for primary care physicians and orthodontists when attempting to determine when surgery is indicated.

For the current research, the team chose to do a longitudinal study, which follows specific individuals over time, instead of an easier cross-sectional study, which observes various age groups at once. “Although more intensive than cross-sectional studies, longitudinal observational studies are more suitable for assessing the complex growth patterns seen in individuals,” says lead author Takayoshi Ishida.

The researchers obtained lateral cephalometric radiographies which are standardized and highly reproducible from 90 samples (same individuals) from a total of 23,133 patient database. For each individual, the adenoid and tonsil sizes were measured at five developmental stages: lower primary school (age 8), upper primary school (age 10), junior high school (age 13), senior high school (age 16), and young adult (age 19). The researchers found that the size of the adenoids and tonsils did not significantly vary among age groups, except when comparing the oldest with the youngest groups (Fig 2).

The previous understanding may have arisen because the surrounding regions of the throat also grow rapidly in teenagers “We found that, in actuality, the airway itself grows bigger, making the fraction taken up by the adenoids and tonsils smaller.” says senior author Takashi Ono. The work is published in Scientific Reports as “Patterns of adenoid and tonsil growth in Japanese children and adolescents: A longitudinal study.” (DOI:10.1038/s41598-018-35272-z)

Figure 1.A Landmarks of the nasopharynx, oropharynx, and hypopharynx.

Abbreviations: Aa, anterior medial point of the atlas; AAL, anterior atlas line (line perpendicular to the palatal line registered on the anterior medial point of the atlas); ANS, anterior nasal spine; Ba, basion; C2, second cervical vertebra; C3, third cervical vertebra; C4, fourth cervical vertebra; Et, epiglottis; EtL, epiglottis line (line parallel to the palatal line registered on the most superior point of the epiglottis); PL, palatal line (line from the anterior nasal spine to the posterior nasal spine); PML, pterygomaxillary line (line perpendicular to the palatal line registered on the pterygomaxillon); PNS, posterior nasal spine; Ptm, pterygomaxillary fissure; SpL, sphenoid line (line tangential to the lower border of the sphenoid registered on the basion).

Figure1.B Definitions of the adenoid (Ad) and tonsil (Tn).

The partially shaded region represents the Ad area, and the part in solid colour represents the Tn area.

Figure 2. Age-dependent changes in the adenoids (Ad) and tonsils (Tn).

Error bars denote 95% confidence interval determined by bootstrap analysis of 1000 iterations.

A) Age-dependent changes in the adenoids (Ad). A comparison of the Ad among the age groups revealed no significant changes. (347.55 ± 12.52, 346.22 ± 12.63, 355.41 ± 14.51, 316.62 ± 14.38, and 274.48 ± 13.03 mm2 in the lower primary school, upper primary school, junior high school, senior high school, and young adult groups, respectively).

B) Age-dependent changes in the tonsils (Tn). A comparison of the Tn among the age groups revealed no significant changes. (161.34 ± 9.54, 152.82 ± 9.35, 145.46 ± 9.59, 127.64 ± 8.48, 110.97 ± 8.19 mm2 in the lower primary school, upper primary school, junior high school, senior high school, and young adult groups, respectively).

Summary:

Correspondence to:

Department of Orthodontic Science,

Graduated School of Medical and Dental Sciences,

Tokyo Medical and Dental University(TMDU)

E-mail: takaorts(at)tmd.ac.jp